Nigeria has the world’s largest electricity access deficit, with 86 million people left unconnected in 2022, according to the IEA. To counter the national grid’s weaknesses and significant economic costs, individuals and particularly industrial users are increasingly turning to self-generated power.

Nigeria’s unreliable power grid is costing the country’s economy an estimated 5% to 7% of its GDP, or about $25 billion annually in economic losses, according to the World Bank. Facing these chronic weaknesses, captive power — electricity generated directly by companies or institutions for their own use — has become a critical solution.

These installations, which use either thermal power plants or solar energy, already total over 6,500 megawatts (MW), a volume greater than the national grid’s current output, estimated at 4,500 to 5,000 MW. The Dangote Group, which generates more than 1,500 MW for its industrial needs, is one of more than 200 companies and institutions relying on this alternative. This trend could accelerate in the coming years, particularly due to the potential of solar energy.

A 2023 study by the Rocky Mountain Institute suggests that Nigeria’s commercial and industrial captive solar energy market could attract $6.5 billion in investments by 2030. The study identified more than 75,000 high-demand and 1.2 million low-demand customers, some of whom would be eligible for solar power, for a total estimated demand of 3.4 gigawatts (GW). Several projects are already operational, such as the 10.3 MW installed across eight Nigerian Bottling Company factories.

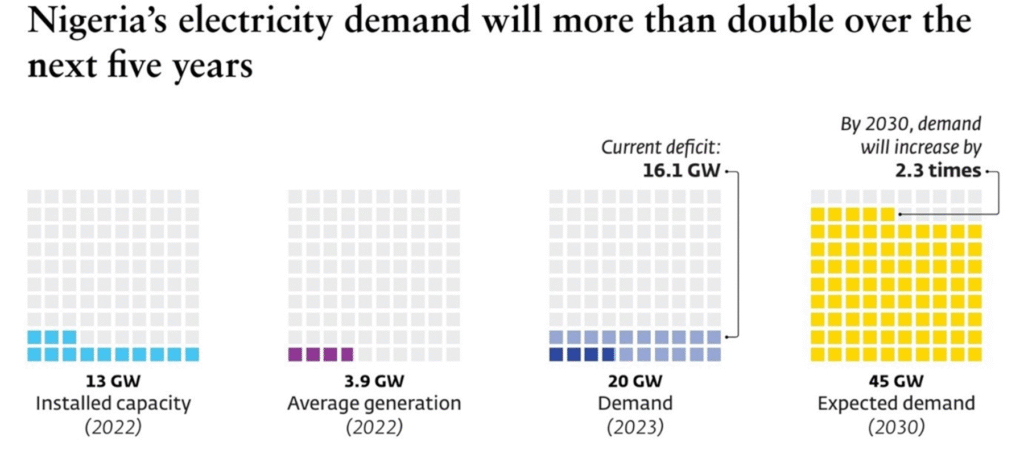

In addition to the national grid’s chronic unreliability, which experienced 12 collapses in 2024, the growth of these solutions is driven by the direct impact of power outages on productivity. The World Bank notes that companies with an unstable power supply suffer greater revenue losses. With a total demand estimated at 20 GW in 2023, and expected to more than double to 45 GW by 2030, the use of captive electricity is an essential lever to support growth.

However, the World Bank believes the sustainability of this market will also depend on Nigeria’s ability to address certain regulatory and financial obstacles. Country and sector risks continue to deter some private investors, who perceive the Nigerian electricity market as highly risky, leading to a higher cost of capital or a reduced willingness to invest.

Furthermore, developers of projects exceeding 1 MW must navigate a complex and cumbersome authorization process, which slows down investments. The 1 MW threshold set by the 2023 mini-grid law limits the development of projects large enough to power major communities or industrial users. The federal government plans to install 12,000 mini-grids by 2030, which translates to about 2,000 permit applications to process each year. Raising this threshold to 5 MW, as recommended by the World Bank, would reduce unit costs, speed up procedures, and more effectively meet demand.