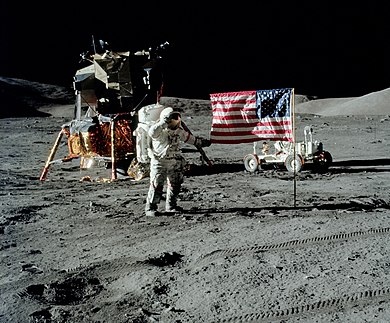

December 11, 1972: Apollo 17 Lands at Taurus-Littrow

Apollo 17 (December 7–19, 1972) was the eleventh and final mission of NASA‘s Apollo program, the sixth and most recent time humans have set foot on the Moon or travelled beyond low Earth orbit. Commander Gene Cernan and Lunar Module Pilot Harrison Schmitt walked on the Moon, while Command Module Pilot Ronald Evans orbited above. Schmitt was the only professional geologist to land on the Moon; he was selected in place of Joe Engle, as NASA had been under pressure to send a scientist to the Moon. The mission’s heavy emphasis on science meant the inclusion of a number of new experiments, including a biological experiment containing five mice that was carried in the command module.

Mission planners had two primary goals in deciding on the landing site: to sample lunar highland material older than that at Mare Imbrium and to investigate the possibility of relatively recent volcanic activity. They therefore selected Taurus–Littrow, where formations that had been viewed and pictured from orbit were thought to be volcanic in nature. Since all three crew members had backed up previous Apollo lunar missions, they were familiar with the Apollo spacecraft and had more time for geology training.

Launched at 12:33 a.m. Eastern Standard Time (EST) on December 7, 1972, following the only launch-pad delay in the course of the whole Apollo program that was caused by a hardware problem, Apollo 17 was a “J-type” mission that included three days on the lunar surface, expanded scientific capability, and the use of the third Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV). Cernan and Schmitt landed in the Taurus–Littrow valley, completed three moonwalks, took lunar samples and deployed scientific instruments. Orange soil was discovered at Shorty crater; it proved to be volcanic in origin, although from early in the Moon’s history. Evans remained in lunar orbit in the command and service module (CSM), taking scientific measurements and photographs. The spacecraft returned to Earth on December 19.

The mission broke several records for crewed spaceflight, including the longest crewed lunar landing mission (12 days, 14 hours),[7] greatest distance from a spacecraft during an extravehicular activity of any type (7.6 kilometers or 4.7 miles), longest time on the lunar surface (75 hours), longest total duration of lunar-surface extravehicular activities (22 hours, 4 minutes),[8] largest lunar-sample return (approximately 115 kg or 254 lb), longest time in lunar orbit (6 days, 4 hours),[7] and greatest number of lunar orbits (75).[9]

Crew and key Mission Control personnel

In 1969, NASA announced[11] that the backup crew of Apollo 14 would be Gene Cernan, Ronald Evans, and former X-15 pilot Joe Engle.[12][13] This put them in line to be the prime crew of Apollo 17, because the Apollo program’s crew rotation generally meant that a backup crew would fly as prime crew three missions later. Harrison Schmitt, who was a professional geologist as well as an astronaut, had served on the backup crew of Apollo 15, and thus, because of the rotation, would have been due to fly as lunar module pilot on Apollo 18.[14]

In September 1970, the plan to launch Apollo 18 was cancelled. The scientific community pressed NASA to assign a geologist, rather than a pilot with non-professional geological training, to an Apollo landing. NASA subsequently assigned Schmitt to Apollo 17 as the lunar module pilot. After that, NASA’s director of flight crew operations, Deke Slayton, was left with the question of who would fill the two other Apollo 17 slots: the rest of the Apollo 15 backup crew (Dick Gordon and Vance Brand), or Cernan and Evans from the Apollo 14 backup crew. Slayton ultimately chose Cernan and Evans.[11] Support at NASA for assigning Cernan was not unanimous. Cernan had crashed a Bell 47G helicopter into the Indian River near Cape Kennedy during a training exercise in January 1971; the accident was later attributed to pilot error, as Cernan had misjudged his altitude before crashing into the water. Jim McDivitt, who was manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office at the time, objected to Cernan’s selection because of this accident, but Slayton dismissed the concern. After Cernan was offered command of the mission, he advocated for Engle to fly with him on the mission, but it was made clear to him that Schmitt would be assigned instead, with or without Cernan, so he acquiesced.[15][16] The prime crew of Apollo 17 was publicly announced on August 13, 1971.[17]

When assigned to Apollo 17, Cernan was a 38-year-old captain in the United States Navy; he had been selected in the third group of astronauts in 1963, and flown as pilot of Gemini 9A in 1966 and as lunar module pilot of Apollo 10 in 1969 before he served on Apollo 14’s backup crew. Evans, 39 years old when assigned to Apollo 17, had been selected as part of the fifth group of astronauts in 1966, and had been a lieutenant commander in the United States Navy. Schmitt, a civilian, was 37 years old when assigned Apollo 17, had a doctorate in geology from Harvard University, and had been selected in the fourth group of astronauts in 1965. Both Evans and Schmitt were making their first spaceflights.[18]

For the backup crews of Apollo 16 and 17, the final Apollo lunar missions, NASA selected astronauts who had already flown Apollo lunar missions, to take advantage of their experience, and avoid investing time and money in training rookies who would be unlikely to ever fly an Apollo mission.[19][20] The original backup crew for Apollo 17, announced at the same time as the prime crew,[17] was the crew of Apollo 15: David Scott as commander, Alfred Worden as CMP and James Irwin as LMP, but in May 1972 they were removed from the backup crew because of their roles in the Apollo 15 postal covers incident.[21] They were replaced with the landing crew of Apollo 16: John W. Young as backup crew commander, Charles Duke as LMP, and Apollo 14’s CMP, Stuart Roosa.[18][22][23] Originally, Apollo 16’s CMP, Ken Mattingly, was to be assigned along with his crewmates, but he declined so he could spend more time with his family, his son having just been born, and instead took an assignment to the Space Shuttle program.[24] Roosa had also served as backup CMP for Apollo 16.[25]

For the Apollo program, in addition to the prime and backup crews that had been used in the Mercury and Gemini programs, NASA assigned a third crew of astronauts, known as the support crew. Their role was to provide any assistance in preparing for the missions that the missions director assigned then. Preparations took place in meetings at facilities across the US and sometimes needed a member of the flight crew to attend them. Because McDivitt was concerned that problems could be created if a prime or backup crew member was unable to attend a meeting, Slayton created the support crews to ensure that someone would be able to attend in their stead.[26] Usually low in seniority, they also assembled the mission’s rules, flight plan and checklists, and kept them updated;[27][28] for Apollo 17, they were Robert F. Overmyer, Robert A. Parker and C. Gordon Fullerton.[29]

Flight directors were Gerry Griffin, first shift, Gene Kranz and Neil B. Hutchinson, second shift, and Pete Frank and Charles R. Lewis, third shift.[30] According to Kranz, flight directors during the program Apollo had a one-sentence job description, “The flight director may take any actions necessary for crew safety and mission success.”[31] Capsule communicators (CAPCOMs) were Fullerton, Parker, Young, Duke, Mattingly, Roosa, Alan Shepard and Joseph P. Allen.[32]